By Milliam Murigi

Developing countries risk being left behind in the new green economy despite being richly endowed with critical minerals crucial for energy transition, a new report has revealed.

The report, titled “Towards a New Green World: Critical Minerals—Moving Up the Value Chain, by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) reveals that the ongoing global transition toward renewable energy is repeating old patterns of resource extraction and dependency.

While developing nations provide the raw materials needed for wind turbines, solar panels, and electric vehicles, the real profits are reaped elsewhere.

“Developing countries continue to export raw materials while industrialized nations capture most of the value through refining, manufacturing, and innovation,” reads part of the report.

According to the report, from copper and cobalt to lithium and rare earth elements, the mineral wealth of the Global South powers the world’s green ambitions, but the benefits rarely reach those who mine them.

For instance, Chile contributes around 30 percent of the world’s raw copper exports, yet captures only 12 percent of the revenue from processed copper.

Australia supplies more than 76 percent of global raw lithium, but China earns nearly a quarter of the world’s processed lithium export revenues. Meanwhile, Indonesia produces over 60 percent of mined nickel, but China and Japan control 75 percent of global refining capacity.

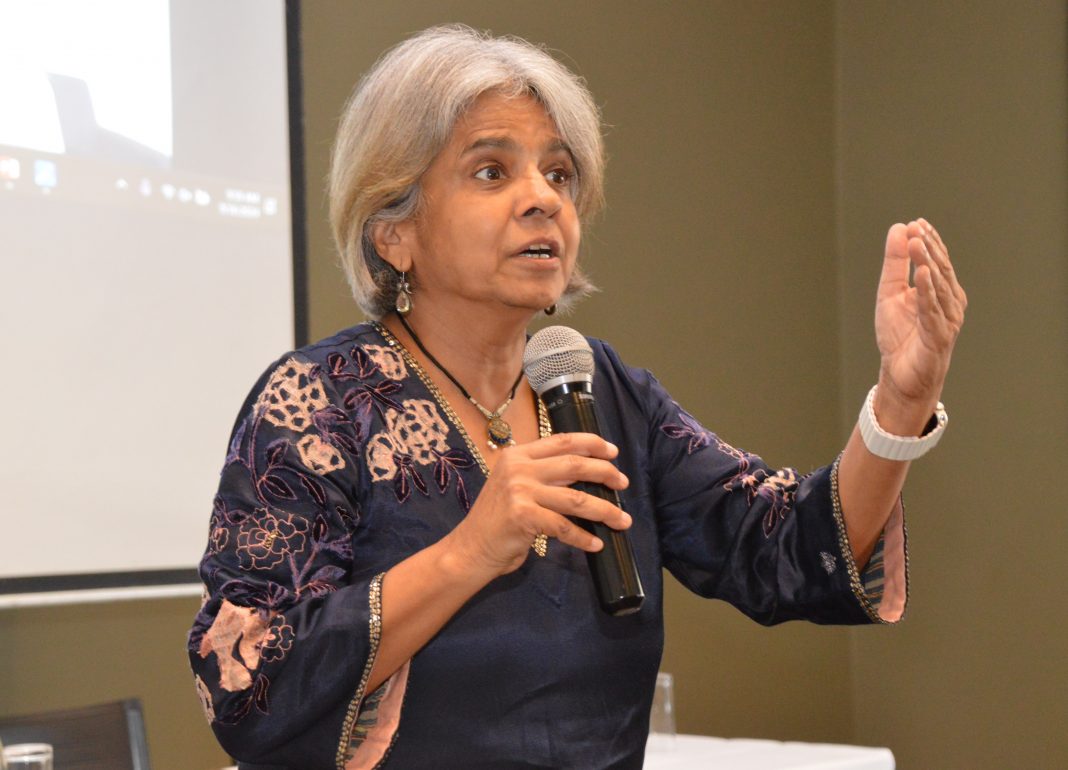

“Countries need an economic stake in the green transition, which requires domestic manufacturing and job creation. For this, we must also reset global trade and finance rules for localisation and value addition. There is an opportunity to rethink these rules so that distributed local-led production systems can become the basis of green industrialisation,” said Sunita Narain, CSE’s Director general.

The report warns that if developing countries remain stuck in the role of raw material suppliers, they could face new economic vulnerabilities. Heavy reliance on mineral exports exposes economies to commodity price shocks, environmental degradation, and “boom-and-bust” cycles that weaken long-term development.

For example, Chile’s current account balance surged twenty-fold in 2004 during a global copper price spike, only to contract sharply when prices fell again.

However, the report also highlights emerging success stories showing that change is possible. Indonesia, for example, banned the export of nickel ore in 2014 and introduced incentives for companies investing in local smelting and refining. This policy attracted over US$20 billion in downstream projects and transformed the country into the world’s largest refined-nickel producer.

“In Africa, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have formed a joint battery value chain partnership aimed at local processing of nickel, manganese, and cobalt critical inputs for electric vehicle batteries. Similarly, the African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy, launched in 2025, seeks to ensure that Africa moves from being merely a supplier of raw materials to an integrated partner in global value chains,” the report reads.

To prevent the green transition from becoming another form of exploitation, the report proposes four strategic pillars for the Global South. First, sufficiency encouraging sustainable consumption and reducing over extraction. Second, recycling and circularity. Investing in technologies to recover minerals from e-waste and used batteries.

Third, regional cooperation, through frameworks like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), to harmonize standards and attract investment. Fourth, economic diversification, to reduce dependence on single-resource exports and build resilience against price shocks.

“The global green transition risks reproducing old inequities under a new climate-friendly banner, unless the Global South is empowered to capture greater value, diversify its economies, and shape the governance of emerging green industries,” says Avantika Goswami, programme manager, climate change, CSE.

The study calls on policymakers to embed justice, human rights, and environmental safeguards in mineral governance. It also urges stronger international collaboration that enables fair financing, technology transfer, and equitable participation in the green value chain.

“The future green economy must not mirror the inequalities of the old one. The Global South needs not just a greener world but a fairer one, with economic resilience at its core, in hand with climate action,” says Narain.